I first encountered Tatiana Bilbao’s work in person in 2015, when she exhibited her now much-acclaimed flexible prototype for social housing at the Chicago Architecture Biennial. The house can be built for as little as $8,000, but its modular design guarantees true adaptability in terms of size, environment, and cultural fit. Tatiana’s practice would be noteworthy alone for that impulse toward equity and advocacy, but other aspects jump out, too. There’s a commitment to honest materials, a dramatic sense of geometry, and—perhaps most notable—a bone-deep belief in the power of collaboration.

We talked with Tatiana from her studio in Mexico City, a natural light–filled space where conference room partitions are transparent and double as display panels for project drawings and plans. True to Tatiana’s self-professed preference for collaboration, the rooms were bustling with coworkers, fellow architects, and researchers. She took time out of her busy schedule to discuss an array of topics, including her technological agnosticism, how she inherited political consciousness from her leftist architect grandfather, and the radical concept of considering the thoughts of your building’s future inhabitants.

Your practice has a strong sense of advocacy, especially in terms of considering affordability as an element of architecture. How do you go about that?

I believe in architecture for human beings, and human beings are everyone. All of us—high income, low income, medium income, any gender, any race, any human being. That’s why my work ranges so much, because human beings range so much.

- Tatiana designed her flexible housing prototype—which can be expanded and reduced—to help tackle Mexico’s housing crisis. Photo by Santiago Arau.

- …In use in Ciudad Acuña. Photo by Santiago Arau.

Tell me a little about how you approach collaboration. I know with the social housing prototypes that were built in Ciudad Acuña and elsewhere you did outreach to the people who would be living in those spaces.

The design for that house was a commission from a financial institution. They asked us to design a house that could be inserted in the government’s program for social housing. It’s housing for those who cannot enter into the system of social housing in Mexico. In Mexico’s system of social housing, you have to have a formal job. You have to be part of the system. But more than 60% of the population does not have a formal job, so those people cannot enter the system. But there’s a constitutional obligation to provide dignified housing for all, so they created these other programs for people who don’t have formal jobs to broaden the spectrum of providing housing from the government.

This system is where we have to design a house; there were a lot of constraints and rules and codes to meet. There are hundreds of models out there people can choose from—and I thought it was going to be difficult to provide a different solution than what was already in the market; I thought they were all explored. [I realized] if we’re going to provide a solution, let’s provide bigger to start with, because they’re always the minimum the government allows. And they need to be adaptive to different situations.

- Photo by Ana Hop.

- Photo by Ana Hop.

These [older] models are one single housing model for people who, say, live in the tropical weather, or the desert, or in the forest. We have a huge country, almost the size of Europe, and we cannot provide a single model for all those types of weather and culture that occur throughout the country. For example, in Chiapas they cook and eat outside, but in Chihuahua they don’t. It’s a completely different model of living and using space. That’s very, very important. Nowadays, in the 21st century, we are imposing people to live the same way—and we are not the same people everywhere. Allowing [people] to have a house that’s a platform for individuals to create their own ideas of living space is what we want to provide.

The other thing is, I really wanted it to be expandable. If you grow, or you’re doing better, or the economy’s doing better, and you want to add a space to your house, all the [previous] models in the market didn’t provide that opportunity. It could be a separate unit, or a unit on top of the unit that was built in the first place. If there was a small solution available within the constraints, I would do it. I found out it was pretty easy. We didn’t have to charge for each house that was built. It was very easy to move within the constraints.

Tatiana’s studio built nearly two dozen of her social housing models and is poised to expand them further. Photo by Santiago Arau.

I also realized we needed to talk to the people who were going to live in the house. We went to do a lot of interviews with those people to really understand what they wanted. We realized they didn’t care about the planning. In certain areas, it was very important that the house really looked like a house, really looked finished. The majority didn’t want a house that didn’t feel like solid construction. In Mexico we even have a word for construction that’s made with raw materials like blocks or rocks. People really wanted [a finished look]. The semi-urban areas and urban areas didn’t mind more temporary materials, because they didn’t see this as their final house. They saw this as a step. So we then spent a long time designing a model that would feed all these needs. Then we tested, fixed some flaws. We were able to build 23 in the north of the country. Now we’re waiting to build them massively.

[rp4wp]

Is there a project of yours you consider most representative? One that combines all those senses of collaboration, advocacy, and geometry?

I think I’m still searching for that. That’s a question like which of your children do you love the most? I cannot answer that. One of the projects I can definitely say I’m proud of is the Botanical Garden [in Culiacán, Mexico]. We’ve been working on that project since 2005; in June it’s going to be 14 years. We’ve been working continuously. It’s very slow, but that allows us to understand what goes well and what doesn’t go so well, and how can we build in this environment? I think that’s what architecture needs to last. In the past, because construction took so long, the majority of a city’s buildings were built over a generation. And they have lasted generations. That’s something very beautiful, but it’s an opportunity we don’t have often. Having time is a gift, and I think that’s what we have in the garden. We’re using what we learned from the garden on other projects.

“I’m still the naive architect who wishes architecture could change everything.”

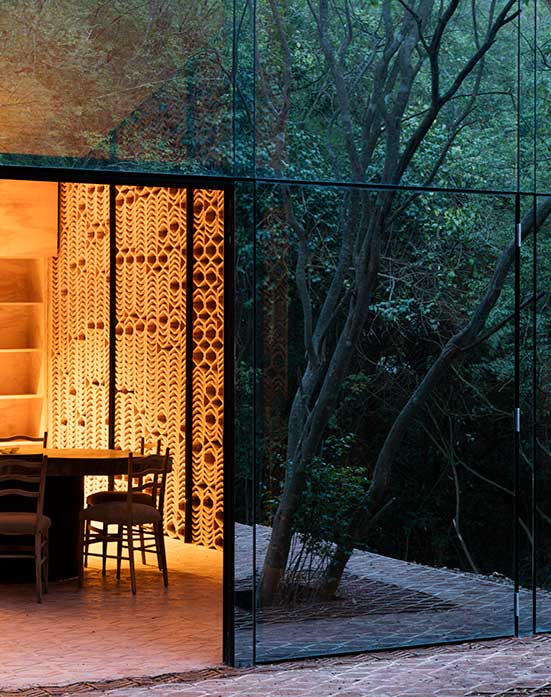

- One building in the Los Terrenos project has a mirrored glass-clad exterior. Photo by Rory Gardiner.

- It offers beautiful woodland views from inside. Photo by Rory Gardiner.

Have you noticed any appreciable difference in challenges between clients, whether it’s government, a university, or a private client? Is there a baseline approach or is everything unique?

This is a question that comes up I think because I work constantly. One of the reasons I think they’re all different is because every human being is different. I really try to become that other human being who is going to inhabit or use this place. Aesthetically speaking, we use geometry and we pay attention to materials. I think architecture is built on language; it’s a means of communicating things to other human beings. There has to be communication with others. By using recognizable geometry and materials that are true and clear and open and reachable and able to be seen, I think this is being honest. When you see brick, it’s brick. That’s the structure’s aesthetic final definition. When you see concrete, that’s it. And when you see earth, it’s earth. We’re not covering materials on top of each other.

Photo by Rory Gardiner.

A glass wall along a bedroom in Los Terrenos can be opened to let the space directly meet the outdoors. Photo by Rory Gardiner.

Is that something your grandfather’s firm shaped?

I never met my grandfather. He died when I was 11. But the first things I learned about my grandfather, and almost all my memories, almost my inheritance from him, were political ideas. He was a minister in the failed Spanish Republican government. Eventually he was a refugee in Mexico—this is why I’m Mexican—so I was born with that. I was always very aware of his political ideas and ideals, and then when I was older I started to realize, first he was a very political architect, then he came to the center of political ideals in the form of being a minister. I think he was first and foremost an architect. But I didn’t grow up where he built the majority of his work. I was there once. I visited, but I was not so aware. But I had uncles and cousins that were architects and I grew up with those things. My grandfather was very, very ambitious, for sure, and he had been employed for social welfare, but I think other than that everything is completely different. We also live in a totally different context and situation, and I believe that makes it very different.

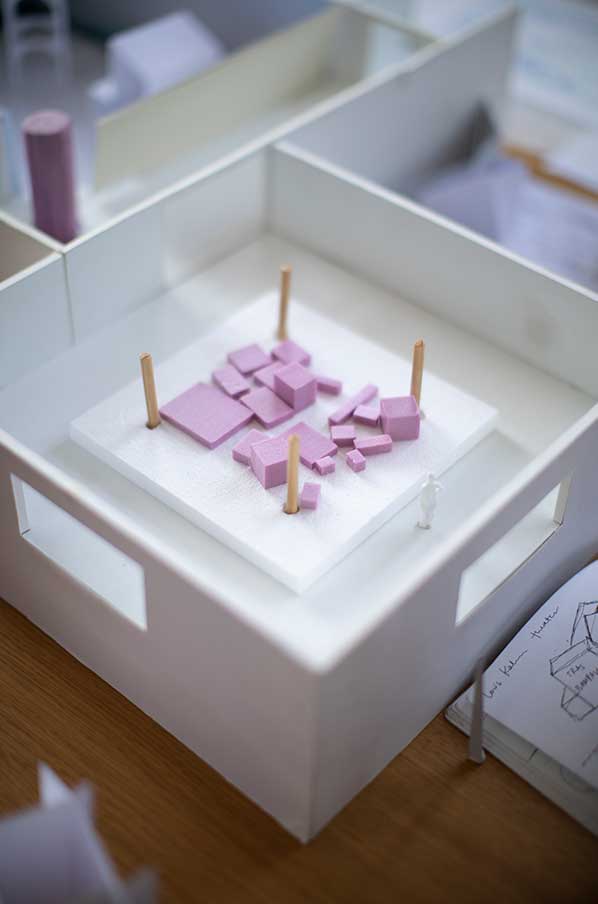

Tatiana uses the glass partition of her Mexico City studio’s conference room to display and consider drawings and renderings. Photo by Ana Hop.

You’ve taught at Yale and Columbia and other institutions. Is there a particular lesson you try to most impress upon students? Do you find yourself learning from the next generation’s approach?

I love teaching. I hate traveling now. I didn’t before. This is why these next years I’m not going to do it. The first thing I tell my students, I present the syllabus and I present the topic of the course, and then the second thing, I say, “This is a subject I’m interested in, too. I’m here to learn. If I don’t learn, I don’t think you learn as much.” So this is what I always hope in the studio. So far for me it’s been great. I’ve also had good feedback from the students. I think that’s a very different way of learning from what I used to have. I used to have these professors where they know everything and I learn everything. But nowadays, my approach, you learn with everybody, learn with each other and learn from each other. I truly believe the more I learn, the more they learn.

And I think students are more open to question the system—actually it’s the other way around—now they always question the system. I think that’s also very good, definitely a different way of learning and seeing life.

- Photo by Ana Hop

- “We needed to talk to the people who were going to live in the house,” Tatiana Bilbao says of her social housing project. Photo by Ana Hop

When I came up, we saw great changes in technology and thought architecture needed to go that way. I think that’s changing radically, and I’m very glad. I still think architecture is something that needs to be physical. They will have incredible technological skills to do whatever they want, but they also need to understand the richness of the hand drawing and the hand model and their strength. This is not something I saw in the generation before me. After me and before now, they were only using a computer and thinking how to digitalize everything in their life, and I’m glad it’s going a little bit back. With technology comes a lot of benefits, but it creates a lot of constraints. The world is physical, not digital.

When you’re working on your own projects, is there a push toward the tactile? Are there a lot of mockups and prototyping?

Absolutely. I personally do not know how to use a computer other than Outlook for my email and Keynote for my presentations. Literally, I don’t use any other thing. I use my hands and my mind. When we start, the first thing is the very broad idea behind it, then we start doing things with our hands. I think that translation—from the mind to the hands to the physical thing—really allows you to understand way better a space. Even if you’re trying to create a space with an impacted geometry. For me, it’s very, very important. In the office we do a lot of manual things all day long.

Do you review as a team? What does that look like?

It’s a very organic process. My sister is my partner and she’s not an architect. She’s an economist, and when she first started working in the office, which was 10 years ago, she couldn’t understand. She’d be there in the midst of a massive operation and she’d be like, “So what’s the process?” I’m like, no, there’s no process. Now we have a good understanding of how to accommodate those two things.

What happens next is testing them toward the main idea we have. We always have that in the back of our head. Whenever something does not work, I’m like, “Guys, we’re not back into our original idea. What was it?” And then go back. Then we test and test and test. Sometimes we have to change the initial idea we were trying to develop. I don’t understand why some projects go more quickly than others. There’s not a single thing I can say that repeats within those projects that go quickly or not.

Tatiana goes over details with, from left to right, Sebastian Vizcaino, Ayesha Ghosh, Isaac Monterrosa, and Alba Cortes. Photo by Ana Hop.

Photo by Ana Hop.

I imagine as you and your firm gain more renown clients come with higher budgets. How does that impact how you work?

I think what we’re getting are budgets that really create more impact, bigger impact, and for me, there’s a responsibility of doing things better. With every project we need to think how can we impact even more? How can we improve more lives of people? How can we improve their relationships? How can architecture do that? I know architecture can’t solve the world, but I wish it would. I’m still the naive architect who wishes architecture could change everything. But I do believe the more we do that, the better it can perform. We have an incredible balance of projects that come to us. We’re at a special moment where we’re able to do a project like a house for $8,000 and still do an aquarium for much more. I think we’re in a good spot.

Do you have any contemporaries you’re particularly fond of, feel a kinship with, or who inspire you?

Colleagues? There are many. I think there’s an incredible creative group of people in Mexico around me, and it’s not only architects. One of my very best friends who I’ve worked often with is Derek Dellekamp. I’m always very eager to collaborate with people, always looking for people who are doing things I admire so much, and I think, “That was a great idea. How’d they do that?” and try to call them. I’m like, let’s do something together! That’s how I started collaborating with MAIO Studio in Barcelona, who I much admire. It’s about 90% success; 10% that aren’t completed.

It’s that simple? Find a number and ring them up?

Yeah, literally. Just call them up!

- Rammed earth and wood feature prominently in Tatiana’s Los Terrenos. Photo by Rory Gardiner.

- The project consists of a small group of buildings situated in Nuevo León. Photo by Rory Gardiner.

Do you feel an obligation to advocate for other female architects?

When I started doing lectures, the first question was always that, what’s the difference when it’s a female architect, and I’m like, I’m not even going to answer these questions, because if I answer them, it implies I’m different. I’m not different. But then one day, my friend Derek Dellekamp, who I mentioned before, told me, “You know, Tatiana, I understand where your concerns come from. But you have to answer these things. Because who was there before you? Name one Mexican woman architect before you. Who was your woman role model in architecture, in Mexico?” I’m like, “Hmmm, well, nope, no one.” So he said, “I’m sorry, but that’s why it’s your turn to advocate.”

This is definitely a topic my generation has to talk about. I don’t necessarily need to pick women to collaborate with. We have more opportunity as women now. And I have more opportunities with people requesting projects or inviting me to exhibitions only because I’m a woman and not only because of my work. All those things work together. For me it’s been way more of an opportunity than a constraint. There needs to be balance, but sometimes to get balance you need to go all the way to the other end of the spectrum. I like to think one day gender and race will be like hair color.

Is there anything you’re working on now that you’re particularly excited about?

I’m working on a monastery, which is such a beautiful project, and I’m so much looking forward to that. But there’s also a very important, big exhibition of my work coming up in October at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, in Copenhagen, which will travel as well.

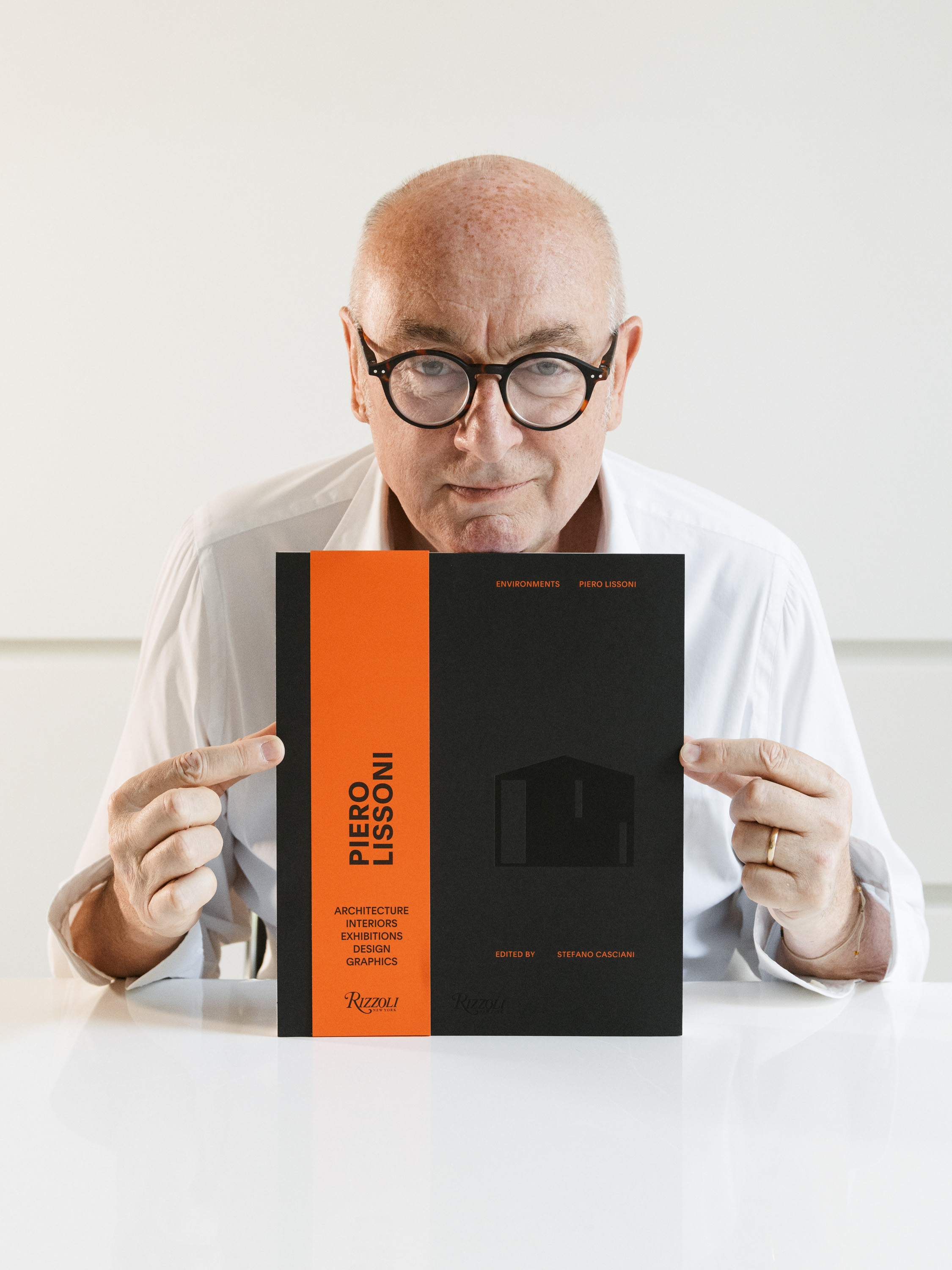

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of Sixtysix with the headline “Tatiana Bilbao Wants to Believe Architecture Can Save Us.” Subscribe today.